THE CHINQUAPIN RANGERS

The Chinquapin Rangers were a cavalry company of partisan rangers formed under the Partizan Ranger Act, which was passed by the Confederate Congress on April 21, 1862. The Company was formed by Captain William Gardner Brawner in May of 1862 at Buckhall in Prince William County, Virginia. The Confederate Army had just recently vacated the area and it was left undefended at that time. Clearly, this unit was formed at least in part to fill that void. Their more formal name was the “Prince William Partisan Rangers” or just the “Prince William Rangers”. When Confederate companies of troops were formed, the men elected their officers by popular vote. The Chinquapin Rangers enrolled 131 men throughout the war. Most of these men were from the Bull Run-Occoquan area of southern Fairfax County and from the north-central and eastern part of Prince William County. They were the primary local unit in and from this area.

Many local names were represented on the roster of the Chinquapin Rangers. Among the rangers there were 8 men named Davis, 7 men named Cornwell, 5 men named Kincheloe, 5 men named Mayhugh. There were 3 rangers each named Brawner, Carter, Fairfax, Hixson, Lynn, Pettit, Reid, Richardson and Tillett. There were 2 rangers each named Beach, Colbert, Cole, Crouch, King, Lowe, Marshall, Murphy, Payne, Shepherd, Spittle, Stone and Wilt.

The Chinquapin Rangers derived their name from the imagination of one of their own members, Private James E. Stone. When asked by a lady the name of his company, Stone, in a spirit of fun, told her that they were the Chinquapin Rangers. That name followed them ever after. A chinquapin is a deciduous, bushy, dwarf chestnut that grows locally and has a small edible nut.

In September, 1862 they were formally mustered into the Confederate service as Company H of the 15th Virginia Cavalry. They spent their time during the War Between the States doing scouting work for J. E. B. Stuart, raiding behind the Union lines and performing spy and reconnaissance missions as an independent company. In order to ride in the Confederate cavalry you had to provide your own mount. That meant you had to either own a horse or else liberate a horse from the Yankees.

In September, 1862 they were formally mustered into the Confederate service as Company H of the 15th Virginia Cavalry. They spent their time during the War Between the States doing scouting work for J. E. B. Stuart, raiding behind the Union lines and performing spy and reconnaissance missions as an independent company. In order to ride in the Confederate cavalry you had to provide your own mount. That meant you had to either own a horse or else liberate a horse from the Yankees.

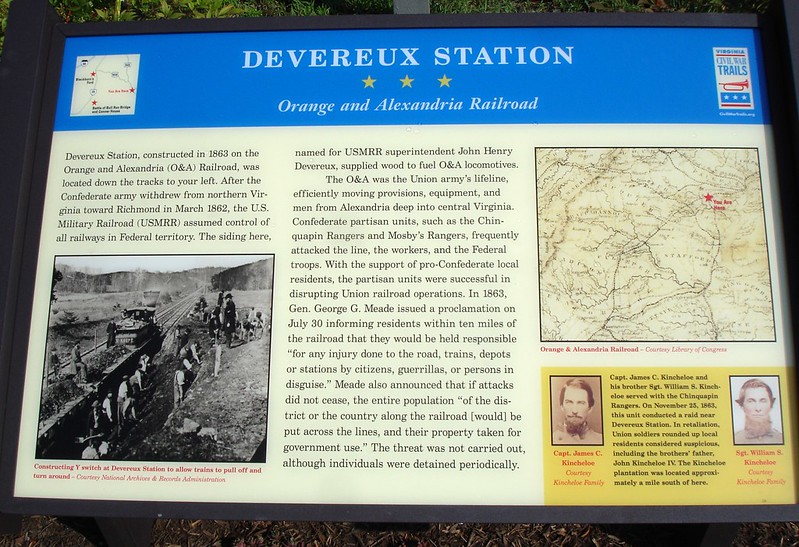

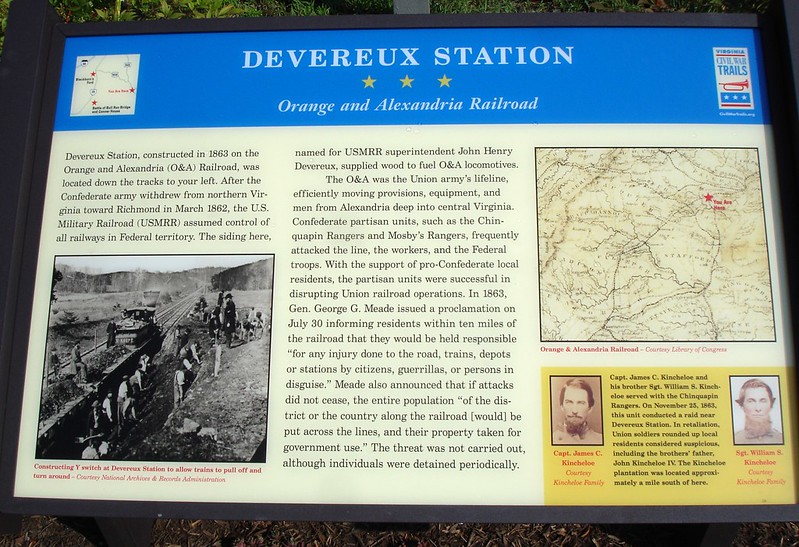

For a significant portion of the War Between the States, the Orange and Alexandria Railroad served as a major supply line for the Union Army of the Potomac on its quest to take Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy.

It appears that one of the first raids of the Chinquapin Rangers was on the afternoon of October 31, 1862 (Halloween) when they derailed a locomotive and 12 cars down the railroad tracks from Devereux Station near Bull Run Bridge. The train went 50 feet down an embankment. No casualties were sustained, but all of the approximately 100 soldiers and woodcutters were taken as prisoners. At that time, they were the only partisan ranger company in the area. John Singleton Mosby did not begin his independent partisan operations until after the Burke Station Raid in late December, 1862.

The Chinquapin Rangers were at the extreme right end of General Lee’s line at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, 1862 helping to guard the Confederate right flank. They were with General W. H. F. “Rooney” Lee’s cavalry brigade. To their left, was the Bowling Green Road and Hamilton’s Crossing on the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad. To their right, was the Rappahannock River. They were in the woods, ravines and gorges in the plain with Massaponax Creek to their rear. Nearby, Major John Pelham of Stuart’s Horse Artillery fired down the Union line on the Union Army’s left flank. Firing and moving several times, Pelham disrupted and provoked the Yankees. He then retired back to the Confederate lines. Elements of the Union Iron Brigade and infantry and artillery of General Abner Doubleday’s Division produced an immediate response. It seems Company H received part of that response. Seven men of their Company were captured. Private George W. Wilt was so severely wounded by a shell that he had to have his left leg amputated. The Chinquapin Rangers sustained some of the only casualties that the Confederate Cavalry had that day. The Union assault at Fredericksburg was delayed and Union forces were tied up by this action. On that day, Major John Pelham of Stuart’s Horse Artillery earned the sobriquet “The Gallant Pelham” from General Robert E. Lee.

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Chinquapin Rangers participated in the Burke Station “Christmas Raid” with 1,800 men of Stuart’s cavalry. In this raid, Stuart took his forces well behind the bulk of Burnside’s Union Army between its encampment and the United States Capitol. On that raid, J. E. B. Stuart sent his famous telegram from Burke Station to Union Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs complaining of the poor quality of the mules he had just captured; saying that those mules seriously interfered with the movement of the captured wagons. The Confederates had surprised the Union telegraph operator, capturing him before he could get off an alarm message. They then listened to some Union communications before sending their own telegram. After they sent their humorous telegram to Meigs, they cut the telegraph wires to disrupt further communications and to aid them in their escape. It was just after the Burke Station Raid that Stuart detailed John S. Mosby with his first independent command in Northern Virginia.

Captain Brawner and the Chinquapin Rangers were at Rector’s Crossroads in Fauquier County when Mosby formed his first company, Company A of what would become the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, on June 10, 1863. After Mosby formed Company A there, the Chinquapin Rangers rode with Mosby and crossed the Potomac River with him attacking a camp of the 6th Michigan Cavalry at Seneca Mills, Maryland on June 11, 1863. It was there that Captain Brawner was killed while gallantly leading the charge. The attached tribute written shortly after Captain Brawner’s death seems to eloquently say it all. Their mission was a success. They routed the Yankees and destroyed their camp before they retired back across the Potomac River with seventeen Federal prisoners and twenty-three captured horses. It could be said that they were the first Confederate soldiers across the Potomac River during the Gettysburg Campaign. After Captain Brawner’s death, First Lieutenant James Cornelius Kincheloe took command of the Company.

![james-cornelius-kincheloe-capt-420818[1]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8345/8251303006_4c3823f094_o.jpg) Captain James C. Kincheloe

Captain James C. Kincheloe

Throughout 1863 and 1864 the Chinquapin Rangers conducted various raiding operations primarily along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad between Prince William County and Accotink in Fairfax County. Raiding in this area pitted them against Corcoran’s Irish Legion, which was stationed at Union Mills to guard the Bull Run Bridge and the railroad. Later, the 4th Delaware Infantry was placed there to guard the railroad. Throughout the War, various other units were stationed up and down the railroad to guard it. As partisan rangers the Chinquapin Rangers operated in their local area, which was part of Union occupied Virginia. Their territory of activity was mostly east and south of Mosby’s Confederacy and only partially overlapped it.

During the war, the Chinquapin Rangers operated within or alongside the Confederate spy and underground communications network. They had contact with Captain Frank Stringfellow, the famous Confederate spy. While riding as part of Mosby’s Rangers near the end of the war these men had contact with Thomas F. Harney of the Confederate Torpedo Bureau. Harney has been described as an “expert in the use of explosives”, also as an “explosives wizard”. Harney was captured shortly after the engagement at Arundel’s Tavern, which occurred the day after Lee surrendered. Some authors suspect Harney was being transported toward Washington, D. C. as part of a covert action team that was going to attempt to blow up the Union War Department and White House and kidnap President Lincoln. Some authors suspect this was authorized and funded by the Confederate Government. I believe that if this were true, the individual rangers themselves would have been merely pawns in this process. My guess is that their mission, if any, would have been to shepherd and funnel the perpetrators into and out of Washington. Speculation about this has made for some interesting print. After Lee surrendered and Lincoln was assassinated public opinion shifted in large part toward reconciliation. Certainly at the end of the war, if anyone had been involved, they would have put as much distance as they could between such a plot and themselves. Their necks would have depended on it!

The Chinquapin Rangers captured Union Major Willard, the fiancé of Confederate spy Antonia Ford, while they were travelling from Fairfax to Washington. Given the choice of letting the romantically inclined couple go or sending Major Willard off to a dreary prisoner of war camp, their guard, Corporal Lewis Woodyard, chose to let them go. Antonia Ford and Major Willard were later married. Many years later, their son, Joseph E. Willard, a one time Lieutenant Governor of Virginia and an Ambassador to Spain, gave Lewis Woodyard a fine gray saddle horse to thank him for his good deed and for his compassion.

One mission they undertook was to personally pick up and deliver a pair of gold spurs sent from Prince George’s County, Maryland admirers to General Robert E. Lee. The gold spurs passed through to Miss Elizabeth Frobel, who brought the spurs to the William S. Reid farm on Franconia Road in Fairfax County. With thousands of Union troops nearby, the gold spurs were picked up and transported by Chinquapin Rangers to General Lee, who received them while he was at a general review of his army near Culpeper Courthouse.

The Chinquapin Rangers participated in the Sangster’s Station Raid with 800-1,000 men primarily belonging to units that would comprise what is known to history as the Laurel Brigade. Because they were local men they served in part as guides through the area. The raiding party rode and struck behind General Meade’s army. This raid began at Hamilton’s Crossing, south of Fredericksburg, on December 16, 1863. The brigade marched to Fredericksburg and crossed the Rappahannock at low tide about twilight. “The fording was deep and some of the men had to swim their horses….About midnight the column halted and rested until morning, when the march was resumed. Rain now set in, at first a drizzle and then a downpour, drenching the men, swelling the streams, and making the roads sloppy and muddy….All day long through the continuous rain, the men, wet to the skin, pushed on through mud and mire.” Moving rapidly, they crossed rain swollen Occoquan at Wolf Run Shoals. In a rare winter thunderstorm, with rain, loud bursts of thunder and lightening they attacked and captured a Union stockade fort at Sangster’s Station in Fairfax County on the Orange and Alexandria railroad. After attending to the dead and wounded, the brigade left with a captured silver bugle and a captured Union regimental flag. Exhausted men and fatigued horses continued the march all night through drenching rain which turned to sleet that benumbed bodies and froze garments. “At sunrise Upperville was reached, and a halt was made to have breakfast and to feed the horses. Here some of the men had to be lifted from their horses, being stiff with cold and their clothing frozen to the saddles. After an hour’s respite the weary march was resumed.” They crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains at Ashby’s Gap and moved along the right bank of the Shenandoah River to Front Royal. “At last when Front Royal was reached there was a halt, and the men went into camp for the first time in forty eight hours, having marched in thirty-six hours more than ninety miles.” The next day they went to Luray. On December 20th, they joined General Early at Mt. Jackson. Not only were men killed and wounded, but other men had drowned crossing the fords in the cold, high water. The Sangster’s Station raid was “….an expedition attended not only with some hard fighting but with a great deal of suffering, the horrors of which made a lasting impression upon every soldier who participated in it.”

Shortly before the Sangster’s Station raid, on November 25, 1863, approximately 25 Chinquapin Rangers conducted a raid at Devereux Station. They captured about 50 mules and 23 men without firing a shot. Immediately following this raid a number of non-combatant citizens were arrested including my great-great grandfather, John Kincheloe, who was arrested November 27, 1863. The 66 year old citizen-farmer spent 5 months in prison as a political prisoner before his release from Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D. C. on May 10, 1864. Forty-nine of the 131 men of the Chinquapin Rangers were captured by the Yankees throughout the war. Some of the captured Chinquapin Rangers along with Mosby’s Raiders and White’s Raiders were considered so dangerous they were moved from Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D. C. to Ft. Warren in Boston Harbor. This was done to isolate them and make any escape harder. They were handcuffed in pairs and transported in a very well guarded special train to New York City. Then, in front of a large crowd, they had to walk through the streets to switch trains to go to Boston. On that walk, Mosby’s Sergeant Alexander G. Babcock spotted the well known editor, Horace Greeley. Babcock lifted his cuffed arm and yelled out to Greeley, “How are you Horace? What do you think of such treatment of prisoners of war?” Rangers George Henry Bradfield and Alexander Colbert died while at Point Lookout Prison. John Colbert and John F. Fairfax died at Fort Delaware P. O. W. Camp. When the War was over, Samuel Cornelius Beach, Thomas Beach, William Edward Carter, George Cornwell, John L. Cornwell and John Peter Davis were released from Fort Warren Prison. William Edward Lipscomb was released at the end of the War from Point Lookout. At the end of the War, Sergeant Samuel H. Jones, Nestor Kincheloe, Armstead T. Marshall, John T. Marshall, John Mayhugh, John Slingerland and George W. Tillett were released from Fort Delaware. At the end of the War, Mountville M. Cornwell, George T. Pettit, William F. Renoe, William H. Smoot and James Wiley were released from Old Capitol Prison.

In 1864, the Confederate Government, in an attempt to rein in some of the mischievous acts of certain partisan rangers, decided to do away with all of those units except Mosby’s partisans and McNeil’s partisans. The Chinquapin Rangers refused to follow orders from the Confederate Government to join the regular cavalry. On September 6, 1864 they were ordered to report to General Fitzhugh Lee in the Shenandoah Valley. Again, they did not comply. They had enlisted as partisan rangers and not as regular soldiers. The Confederate government ordered the company disbanded. They continued to operate locally, as they had done before, until they were finally disbanded on their own accord on December 4, 1864.An attempt to reorganize themselves was officially denied. Against government policy and general orders to the contrary and with full notice of the situation, Mosby bent the rules and enrolled a significant number of the Chinquapin Rangers into his command. Coincidentally, they continued to be Company H. They had been Company H of the 15th Virginia Cavalry. Now they were in Company H of Mosby’s 43rd Battalion of Virginia Cavalry. Mosby chose to take these men into his command because they were local men he knew who had ridden with him before. They were well equipped, well armed, willing, seasoned soldiers who wanted to continue the fight and wanted to defend their home territory. To continue his operations so far behind the lines Mosby needed all of the able bodied local soldiers available. Clearly, he did not want to turn them away or lose them to the general service, where they had been ordered to go.

With Mosby, they were formally made Company H at North Fork in Loudoun County on April 5, 1865. They then rode under their new Captain, Captain George Baylor, and went first to Keyes Switch on the Shenandoah River. There they attacked a camp of the Loudoun Rangers and completely defeated them not far from Halltown, West Virginia. Five or six Federals were killed, forty-five prisoners were captured, seventy horses were taken as well as a number of arms and a lot of equipment. Their last engagement was with the 8th Illinois Cavalry in Fairfax County at Arundel’s Tavern, now known as Brimstone Hill, on April 10, 1865. This occurred one day after General Robert E. Lee surrendered. It was the last engagement of the War Between the States in Virginia. The last casualties of the War in Virginia occurred during this fight.

On April 21, 1865, Colonel Mosby disbanded his command in preference to surrendering them as a unit. The men then sought out their own individual paroles with the Union.

These men fought to the bitter end of a lost cause. They could be considered the last terrorists in Northern Virginia until September 11, 2001. These men were freedom fighters. During the War Between the States, they had fought alongside and against well known people and fighting units. After the War, the Chinquapin Rangers continued to have impact for many years. These partisan rangers, who were considered by some during the war to be featherbed soldiers, road agents and bushwhackers, rose to the occasion becoming in some cases very successful and prominent. The individual rangers, of course, represented a cross section of the community. Not all of the rangers were well read. Twenty-four of them when signing their oaths, paroles and various papers signed with “X” or with marks rather than signatures. Despite this fact an inordinate number of them became leading citizens. Lieutenant Edwin Nelson had been a guide for General Stuart on the Christmas Raid. He was captured on June 21, 1863 while on leave of absence and had been a prisoner of war for most of the balance of the War. Before the War, he had been a constable, Justice of the Peace for Dumfries District (which then also embraced the territory of Coles District) and had been a Deputy Sheriff. In 1878-1879 he represented Prince William in the Virginia House of Delegates. From 1870 to 1887 he was a Deputy Clerk of Court and served as Clerk of the Circuit Court of Prince William from 1887 until his death on February 12, 1911. After Nelson’s death, he was succeeded as Clerk of Court by another Chinquapin Ranger, William E. Lipscomb. Lipscomb served only one month as Clerk of Court until his death. Lipscomb, who would later be a long-serving Judge of the County Court had been captured in 1864 and spent the rest of the War as a prisoner. Judge Lipscomb was a lawyer, Commissioner in Chancery, two-term Mayor of Manassas, several-term member of the Town Council, mercantile businessman, Deputy Clerk of Court under his father, a publisher of the Manassas Gazette and Bail Commissioner. In 1884, Judge Lipscomb was elected to the Virginia Legislature. Another ranger that served in the Virginia Legislature from 1887-1888 was Sergeant Joseph B. Reid. Reid served on the first Manassas Town Council. He owned the Summit House Hotel and bar room in Brentsville. William B. Lynn was a bartender. William Randolph Spittle was a contractor and builder. James Shirley Lynn was a Baptist minister and did missionary work. Sergeant John Henry Butler was Commissioner of the Revenue “above the run” in Prince William County. James Monroe Barbee was Commissioner of the Revenue “below the run” and served as Sheriff of Prince William County. Robert Arrington, who spent a large part of the War as a P. O. W., was Postmaster of Bellefair Mills, Virginia which is just north of the Stafford County line. John Slingerland was a foreman at the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine off of Quantico Creek in what is now Prince William Forest Park. The Cabin Branch Mine was a large base for the economy of the Dumfries area for thirty-one years. The common sulfide mineral pyrite, called iron pyrite or fool’s gold in its pure form is 46.6% iron and 53.4% sulfur. Pyrite, upon being heated, is a major source for the production of sulfuric acid which is an important ingredient of gunpowder and has many other industrial uses. George William Payne worked for about thirty-five years for the Richmond and Danville railroad before he retired and returned to Manassas where he conducted a hotel until his health began to fail. Corporal Charles E. Butler was a carpenter. Lafayette Maddox was a carpenter and a cooper. Elias Crouch, Joseph Crouch, George M. Pettit, Wyleman W. Chappell John H. Renoe, Henry A. Keyes, Wesley Ledman, George W. Lowe, Joseph Mayhugh, Jackson Payne, Marshall A. Carter, John Colbert (died June 21, 1865-P. O. W. Fort Delaware), William H. Wilt (Witt, died March 27, 1863) and Lewis Spittle were coopers. George W. Davis, Sergeant Roy L. Davis, Corporal Levi Hixson, Benjamin Murphy, John L. Reid, Samuel R. Lowe, Armstead Marshall, William D. Davis, Isaac N. Fairfax, Corporal Lewis Woodyard, Edward Shepherd (died March 21, 1863), Joseph B. Shepherd, John Mayhugh, Richard H. Brawner and Robert W. Wilkins were farmers. John L. French inspected cars for the railroad. William H. Smoot was a retail merchant. Sergeant Samuel Houston Jones was a farmer and merchant in Stafford County. Nestor Kincheloe owned the mill at the confluence of Cub Run and Big Rocky Run near Centreville. The mill complex has been variously known over the years as Lane’s Mill, Kincheloe’s Mill and Robinson’s Mill. Mark A. Florence, John L. Cornwell, Leroy Cornwell, Richard H. Cornwell and Alexander Pettit were farm laborers. Lieutenant Wileman Wallace Kincheloe ran Kincheloe’s Store in Brentsville and served as Treasurer of Prince William County. Corporal George W. Hixson was on the first Manassas Town Council. He was also a merchant, lumberman, wagon maker and undertaker. James V. Nash was a farm overseer and served on the Commission that brought the first Courthouse to Manassas. Thomas Fairfax was a businessman in Alexandria. Thomas Stone was a wheelwright. George H. Richardson was a merchant and hotel keeper. Lieutenant Francis C. Davis served as a Justice of the Fairfax County Court from 1852-1860 and again from 1866 through 1868. Davis was a farmer, served as Overseer of the Poor in 1845 and served as an early member of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors. James E. Stone was also a farmer and served as Overseer of the Poor in Fairfax County. Sergeant William Simpson Kincheloe, a farmer that had been a guide on the Sangster’s Station Raid, served as Deputy Treasurer and later as Deputy Sheriff of Fairfax County.

(Sgt. William Simpson Kincheloe)

(Sgt. William Simpson Kincheloe)

Wallace Norman Tansill was a carpenter and was for thirty years a policeman in Fredericksburg. George William Tillett was a stone mason, mechanic and farmer. Henry T. Tillett was a painter and stone mason. John R. Tillett was a leading Manassas businessman, bridge builder and stone contractor. He built the forty foot high Confederate Monument in the Manassas Cemetery, just a short distance from the present day Prince William County Courthouse. Edward Dorsey Cole was detailed for much of the War as a scout and courier for J. E. B. Stuart. After Stuart’s death at Yellow Tavern, Cole was a scout and courier for Robert E. Lee during the fighting around Gaines Mill. Cole then returned to his company, ending the War with Company H of Mosby’s command. Cole became a prosperous merchant, was a long-serving member of the Fredericksburg City Council, was Recorder of Fredericksburg, was on the staff of the Governor of Virginia, was a charter member of the Fredericksburg and Adjacent National Battlefields Memorial Park Association of Virginia, served on the Advisory Board for the erection of the Mary Washington Monument and was appointed to be in charge of the Mary Washington Monument and Park. Sergeant John H. Hammill was a retail merchant in Occoquan. According to his obituary, he was able to get back into business after the War because he retrieved silver he had buried when the War had begun. During the War, he had contracted typhoid fever. Mrs. Adeline Wilkins Lynn, sister of another Chinquapin Ranger housed and cared for him during his illness. When the Yankees searched her house, he played dead, avoided capture and was able to recover in a home rather than possibly expiring in a Union Prison. Redmond Sefrada Kincheloe was a merchant in Warrenton before moving to Wheeling, West Virginia. George Washington Wilt, who had his left leg amputated after the Battle of Fredericksburg, returned to the Confederate Service with Company H. He was paroled May 11, 1865 at Winchester. Wilt married the following summer. He lived to be 76 years old. When he died, October 30, 1912, he was a resident of Church Hill in Richmond and was survived by his wife and 8 children. Wilt is buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond. Captain James C. Kincheloe, who had been a Postmaster of Sangster’s Station and was a farmer, resumed farming south of Clifton after the War. His wife, Susan Texanna Richerson (Richardson) Kincheloe’s obituary in 1928 states that her husband always said she was the best capture he made during his career in the Confederate service. They were married February 8, 1866 at her Mother’s home in Caroline County. Lewis Young lived to be 89 years old, spending his final years at the Robert E. Lee Camp Soldier’s Home, Richmond, Virginia. He died there May 9, 1936 and is buried in Hollywood Cemetery.

The Chinquapin Rangers had served the Confederacy in a unique way, defending their home area, even as it was decimated during a bitter civil war. These men picked up the pieces and resumed fruitful and productive careers.

Private Wellington Fairfax, Co. H 15th VA Cav. After the war ended, he married Vienna P. Davis. He and his wife lived on a farm at Wolf Run Shoals. The house still stands today, the last one on the left at the end of Wolf Run Shoals Road. Wellington is buried in the Fairfax family cemetery north of the house.

Private Jim Stone’s Colt and Remington pistols that he used as a Ranger during the war.

Private Jim Stone’s Colt and Remington pistols that he used as a Ranger during the war.

_______________________________

John T. Kincheloe

August 15, 2012

![600391_10151289457977805_178654211_n[1]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8375/8588573058_cf9df8d553_c.jpg)

![601618_10151289458982805_213426210_n[1]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8507/8587472301_1d8443407b_c.jpg)

![579148_10151289459372805_1627868497_n[1]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8228/8588573144_78e9d2fdb9_c.jpg)

![james-cornelius-kincheloe-capt-420818[1]](https://farm9.staticflickr.com/8345/8251303006_4c3823f094_o.jpg)